In Japan, many disciplines incorporate the word “道(dō),” such as “華道 (ka-dō)” (flower arrangement), “茶道 (sa-dō)” (tea ceremony), “書道 (sho-dō)” (calligraphy), “柔道 (jūdō)” (judo), “剣道 (kendō)” (kendo), and “神道 (shintō)” (Shinto). But why does the word “dō” appear in so many aspects of Japanese culture? And what does “dō” truly mean? Let’s explore its significance.

What Does “Dō (道)” Mean in Japanese?

“Dō (道)” represents a specialized field of study or art, a disciplined approach to mastering a skill, or a way of achieving something in a particular field.

In Japanese, kanji often have multiple readings. “道” can also be read as “michi,” which means road, path, or way. While both “michi” and “dō” signify “way,” the term “dō” carries a deeper, more philosophical meaning tied to personal and spiritual growth.

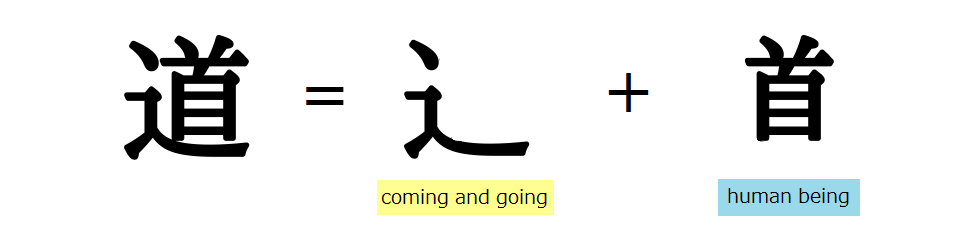

Breaking Down the Kanji for “Dō (道)”

The kanji for “Dō (道)” is composed of two elements. The right side symbolizes the neck or head, representing a human being. The left side represents movement, such as walking, stopping, or traveling back and forth.

Together, the kanji signifies “path” or “way,” initially referring to a physical road (“michi”). Over time, its meaning evolved to reflect the pursuit of supreme goodness—an ideal achieved through continuous effort and self-reflection. In this sense, “dō” not only represents skill improvement but also personal and spiritual growth.

The Difference Between “Dō (道)” and “Jutsu (術)”

In Japanese culture, there are disciplines like “武道 (budō),” “剣道 (kendō),” and “柔道 (jūdō),” which contrast with “武術 (bujutsu),” “剣術 (kenjutsu),” and “柔術 (jūjutsu).” While the techniques in both traditions may appear similar, “術 (jutsu)” is generally regarded as the older, more practical approach, whereas “道 (dō)” is seen as a modernized evolution. For instance, both “剣術 (kenjutsu)” and “剣道 (kendō)” involve mastering sword techniques, engaging in combat, and competing to win. However, “剣道 (kendō)” is a contemporary refinement of “剣術 (kenjutsu)” with a broader focus.

So, what sets “道 (dō)” apart from “術 (jutsu)”? The primary difference lies in their purpose. The aim of “術 (jutsu)” is practical—to defeat an opponent and achieve victory. On the other hand, the goal of “道 (dō)” transcends technique. It seeks to integrate technical mastery with mental discipline, aspiring not only to hone skills but also to cultivate humanity and spiritual growth. In essence, “道 (dō)” builds upon the techniques of “術 (jutsu)” by incorporating a philosophical dimension, focusing on the development of the mind and spirit.

This distinction highlights that “道 (dō)” is not merely about technical training but also about nurturing the mind and character, guiding practitioners toward a higher level of humanity.

Discovering the Practice of “Dō (道)” – From Martial Arts to Artistic Pursuits

What does it truly mean to practice “Dō (道)”? Is there a fundamental difference between “武道 (budō)” – martial arts – and “芸道 (geidō)” – artistic disciplines – even though both share the same “Dō (道)” in their names?

Fortunately, I have had the opportunity to experience both “剣道 (kendō)” – the way of the sword, a form of martial art – and “華道 (kadō)” – the way of flowers, an artistic practice. Drawing from these experiences, I will explore how the essence of “Dō (道)” manifests in both domains and what unites these seemingly distinct paths.

Practicing “Kendō (剣道)” – Discipline Through Swordsmanship

First and foremost, the fundamentals of “剣道 (kendō)”—the way of the sword—are rooted in respecting courtesy and honor, repeatedly practicing strikes, and mastering “型 (kata)”—fixed patterns designed to teach the essential elements of kendō.

Reflecting on my kendō practice, I realize that it embodies the essence of “Dō (道)”—mastering technique through consistent repetition while simultaneously cultivating character. In fact, the concept and purpose of kendō clearly demonstrate this philosophy.

剣道の理念 (The Concept of Kendo)

剣道は剣の理法の修錬による

人間形成の道である

The concept of kendo is to discipline the human character through the application of the principles of the katana (sword).

剣道修練の心構え (The Purpose of Practicing Kendo)

剣道を正しく真剣に学び

心身を錬磨して旺盛なる気力を養い

剣道の特性を通じて礼節をとうとび

信義を重んじ誠を尽して

常に自己の修養に努め

以って国家社会を愛して

広く人類の平和繁栄に

寄与せんとするものである

To mold the mind and body,

To cultivate a vigorous spirit,

And through correct and rigid training,

To strive for improvement in the art of kendo,

To hold in esteem human courtesy and honour,

To associate with others with sincerity,

And to forever pursue the cultivation of oneself.

This will make one be able:

To love his/her country and society,

To contribute to the development of culture,

And to promote peace and prosperity among all peoples.

I have come to realize that mastering the art of “剣道 (kendō)” is not just about perfecting technique—it is a path to personal growth and human development. In fact, this emphasis on character-building and self-improvement is a core principle not only in kendō but also in other forms of “武道 (budō)”—Japanese martial arts.

Practicing “Kadō (華道)” – Art Through Flowers

At its core, the basics of “華道 (kadō)”—the way of flowers—start with learning “花型法 (kakeihō),” a method for flower formation and arrangement. This method introduces practitioners to a wide variety of plants, helping them understand each plant’s unique characteristics while teaching the fundamental rules and techniques for creating harmonious compositions. It even allows beginners to craft stunning arrangements with ease by following defined guidelines for the position, angle, and length of the three main stems.

(Note: This method may not apply universally across all kadō schools, as there are reportedly over 300 different schools.)

“Kadō (華道)” is more than just the arrangement of flowers and plants. It is an art form that takes blooms with only a short time left to live and transforms them into something even more beautiful than their natural state, celebrating their fleeting beauty and the preciousness of life itself. This practice is said to cultivate one’s character, encouraging practitioners to deeply connect with the transient beauty of life.

Through repetitive practice and self-reflection, I have come to understand that kadō embodies the essence of “Dō (道)”—a path of continuous learning and personal growth.

The Power of Repetition in “Dō (道)” Practice

As demonstrated in the examples of “剣道 (kendō)” and “華道 (kadō),” one of the defining features of practicing “Dō (道)” is the repetitive practice of fixed patterns.

This leads to an intriguing question: How does cultural evolution arise from such repetition? At first glance, repeating the same actions might seem stagnant, but the truth is that the various “Dō (道)” practices we see today have clearly evolved from foundational techniques. Repetition serves as a starting point, enabling refinement, innovation, and eventual cultural development.

In the world of “Dō (道),” there is a well-known concept that captures this process: “守破離 (Shu-ha-ri).” This philosophy explains the stages of learning and growth in any discipline. While a deeper exploration of “Shu-ha-ri” deserves its own dedicated discussion, this concept is key to understanding how mastery and evolution coexist within “Dō (道).”

・shu (守) “protect”, “obey”—traditional wisdom—learning fundamentals, techniques, heuristics, proverbs

Shuhari-Wikipedia

・ha (破) “detach”, “digress”—breaking with tradition—detachment from the illusions of self

・ri (離) “leave”, “separate”—transcendence—there are no techniques or proverbs, all moves are natural, becoming one with spirit alone without clinging to forms; transcending the physical

Epilogue: The Spirit of “Dō (道)” in Japanese Education

Japanese education today remains deeply influenced by the spirit of “Dō (道).” A strong emphasis is placed on mastering the basics through repetition, whether in academics, arts, or sports. This repetition lays the groundwork for high levels of technical skill, which is why Japanese practitioners often excel in the fundamentals of various fields.

However, this focus on foundational skills sometimes leads to criticism, with claims that it hinders creativity or the ability to apply those skills in novel ways. Despite this, the enduring value of “Dō (道)” lies in its balance of discipline and self-cultivation.

Personally, I greatly admire and cherish the spirit of “Dō (道)” that continues to shape Japanese culture and education. It is a philosophy that transcends time, connecting us to the traditions and wisdom of the past while guiding us toward personal and collective growth in the future.

Comment List